In 1911 krijgt Walter Gropius zijn eerste grote opdracht: de Fagusfabriek in Alfeld. Dit bouwwerk was erg vooruitstrevend in zijn tijd. Dit is het eerste gebouw waarbij de wanden vrijwel geheel van glas zijn. Ander materiaal dat in de gevel wordt gebruikt is een zandkleurige baksteen.

Dit is een van de eerste gebouwen waarin het functionalisme en de 'nieuwe moderne stijl'te vinden is.

- De AEG's Turbine fabriek had grote invloed op de Fagus fabriek.

Peilers/ glas oppervlakten.

- Gropius beschrijft deze transformatie: "De rol van de muren raakt beperkt tot die van de schermen gespannen tussen de rechtopstaande kolommen, in het kader van het buiten houden van kou, regen en lawaai.

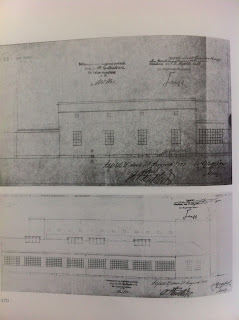

- Het gebouw aan de spoorweg, hoogte van de noord gevel.

- Gebouwd op een kelder, 40cm hoge laag zwarte baksteen, gele baksteen.

- Frames van de ramen, horizontaal dikker en verticaal slanker. Drie verdiepingen, stalen platen.

- Het gebruik van de vloer tot het plafond, ramen op stalen frames die rond de hoeken gaan, zonder zichtbare structurele ondersteuning. En de donkere in combinatie met de gele baksteen. Deze combinatie creerd het effect van lichtheid.

- Gropius noemde dit: vergeestelijking.

- Dit gevoel word versterkt door grotere horizontale dan verticale elementen. Meer ramen op de hoeken en hogere ramen op de laatste vloer.

-Gevel op de noordkant. Ivm het spoor.

-Moderne transport.

The building that had the greater influence on the design of Fagus was AEG’s Turbine factory designed by Peter Behrens. Gropius and Meyer had both worked on the project and with Fagus they presented their interpretation and criticism of their teacher’s work. The Fagus main building can be seen as an inversion of the Turbine factory. Both have corners free of supports, and glass surfaces between piers that cover the whole height of the building. However, in the Turbine factory the corners are covered by heavy elements that slant inside. The glass surfaces also slant inside and are recessed in relation to the piers. The load-bearing elements are attenuated and the building has an image of stability and monumentality. In Fagus exactly the opposite happens; the corners are left open and the piers are recessed leaving the glass surface to the front.[2] Gropius describes this transformation by saying,

"The role of the walls becomes restricted to that of mere screens stretched between the upright columns of the framework to keep out rain, cold and noise"[3]

At the time of the design of Fagus, Gropius was collecting photographs of industrial buildings in the USA to be used for a Werkbund publication. The design of these American factories was also a source of inspiration for Fagus.

Construction history

Fagus Owner

Carl Benscheidt (1858–1947) founded the Fagus company in 1910. He had started by working for Arnold Rikkli, who practised naturopathic medicine, and it was there that he learned about orthopedic shoe lasts (which were quite rare at that time). In 1887 Benscheidt was hired by the shoe last manufacturer Carl Behrens as works manager in his factory in Alfeld. After the death of Behrens in 1896, Benscheidt became general manager of the company, which was on its way to being one of the biggest in that sector in Germany. In October 1910, he resigned from his position because of differences with Behrens’s son.[4]

Commission

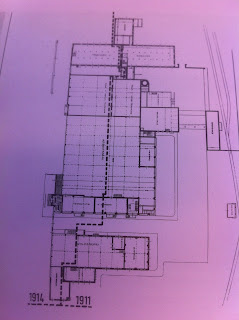

After his resignation Benscheidt immediately started his own company. He established a partnership with an American company acquiring both capital and expertise. He bought the land directly opposite Behrens’s factory and hired the architect Eduard Werner (1847–1923), whom he knew from an earlier renovation of the Behrens factory. Although Werner was a specialist in factory design, Benscheidt was not pleased with the outside appearance of his design. His factory was separated from Behrens’s by a train line and Benscheidt thought of the building’s elevation on that side (north) as a permanent advertisement for his factory.[5][6] On January 1911 he contacted Walter Gropius and offered him the job of redesigning the facades of Werner’s plan. Gropius accepted the offer and a long collaboration began that continued until 1925 when the last buildings on the site were completed.

Construction

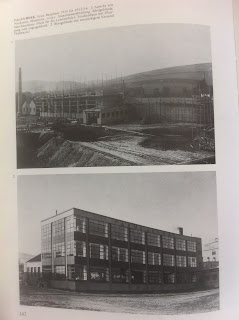

During construction, Gropius and his partner Meyer were under great pressure to keep up to the rhythm of work. Construction started in May 1911 based on Werner’s plans and Benscheidt wanted the factory to be running by winter of the same year. This was achieved in great part and in 1912 Gropius and Meyer were designing the interiors of the main building and secondary smaller buildings on the site.

In order to pay the additional costs of Gropius’s design, Benscheidt and his American partners had decided on smaller building than the one that was actually planned. By winter 1912 it was clear that the factory could not keep up with the number of orders and a major expansion was decided. This time the contract went directly to Gropius and Meyer and, from now on, they were to be the only architects of the Fagus buildings. The expansion practically doubled the surface of the buildings by adding to the street (south) side. This gave the opportunity to create a proper street elevation. Initially the main elevation was considered the north elevation that faced the railway and Behrens’s factory.

Work on the expansion started in 1913 and it was barely finished when World War I broke out. During the war it was possible to do only minor works such as the power house and the chimney stack that became a prominent characteristic of the building complex.

After the war the work continued with addition of minor buildings such as the porter’s lodge and the enclosure wall. During that time the architects, in collaboration with teachers and students from the Bauhaus, designed the interiors and furniture of the main building. They also recommended to Benscheidt various designers for the publicity campaign of Fagus. From 1923 to 1925, the architects were also working on a new expansion, but this never took place. It was not until 1927 that Benscheidt wrote to Gropius to explain that all activities should stop until further notice due to financial difficulties.

In order to pay the additional costs of Gropius’s design, Benscheidt and his American partners had decided on smaller building than the one that was actually planned. By winter 1912 it was clear that the factory could not keep up with the number of orders and a major expansion was decided. This time the contract went directly to Gropius and Meyer and, from now on, they were to be the only architects of the Fagus buildings. The expansion practically doubled the surface of the buildings by adding to the street (south) side. This gave the opportunity to create a proper street elevation. Initially the main elevation was considered the north elevation that faced the railway and Behrens’s factory.

Work on the expansion started in 1913 and it was barely finished when World War I broke out. During the war it was possible to do only minor works such as the power house and the chimney stack that became a prominent characteristic of the building complex.

After the war the work continued with addition of minor buildings such as the porter’s lodge and the enclosure wall. During that time the architects, in collaboration with teachers and students from the Bauhaus, designed the interiors and furniture of the main building. They also recommended to Benscheidt various designers for the publicity campaign of Fagus. From 1923 to 1925, the architects were also working on a new expansion, but this never took place. It was not until 1927 that Benscheidt wrote to Gropius to explain that all activities should stop until further notice due to financial difficulties.

Building

The building that is commonly referred as the Fagus building is the main building. It was constructed in 1911 according to Werner’s plan but with the glass facades designed by Gropius and Meyer and then expanded in 1913. The Fagus building is a 40-centimeter high, dark brick base that projects from the facade by 4 centimeter. The entrance with the clock is part of the 1913 expansion. The interiors of the building, which contained mainly offices, were finished in the mid 20s. The other two big buildings on the site are the production hall and the warehouse. Both were constructed in 1911 and expanded in 1913. The production hall is a one-storey building. It was almost invisible from the railway (north) elevation and acquired a proper facade after the expansion. The warehouse is a four-storey building with few openings. Its design followed closely the original plan by Werner and it is left out from many of the photographs. Apart from them, the site contains various small buildings designed by Gropius and Meyer.Gropius and Meyer were able to enforce only minor changes in the overall layout of the factory complex. Overall, Werner's intended layout for the individual buildings within the complex was carried out; greater uniformity and coherence were achieved, however, through Gropius and Meyer's reductionism in form, material, and color.

Construction System

For many years, people thought that the main building was made of concrete or steel, because of its glass façade. However, during its renovation during the 80s, it became clear that this was not the case. Jürgen Götz, the engineer responsible for the renovation since 1982, describes the construction system like this:

“The main building was erected on top of a structurally stable basement with flat caps. Nonreinforced (or compressed) concrete, mixed with pebble dashing was used for the basement walls, an unfortunate blend unable to support great individual loads. From the basement upward, the building rose in plain brickwork with reinforced wood floors. The ceilings were underpinned with a formwork shell and finished in rough-cast plaster on the services installation side. The floors were composed of planks on loose sleepers – that is, sleepers that were not fixed between the floor joists. Hence, the ceilings in the main building were not continuous shears and thus were unable to fulfill the necessary bracing function.” Bauhaus building in D'The same kind of misunderstanding exists about the glass façade of the building that many writers describe as a curtain wall similar to the one Gropius used for theesau. Götz describes it like this:

“The window openings were intrados frames composed of L beams; the internal membering with horizontal and vertical muntins was differentiated in that all the verticals appeared more slender on the outside, while the horizontals appeared wider. These fames were, however, only floor-to-floor height, screwed to the building on four sides; one string course that reached across the three floors consisted, in fact, of three different sections. Along the side of the building, 3-millimetre-thick steel plates sealed the wedge between window frame and piers.”This description applies only to the main building. Götz note that the other buildings were much simpler and some of them were actually concrete and/or steel constructions.

Design

Although constructed with different systems, all of the buildings on the site give a common image and appear as a unified whole. The architects achieved this by the use of some common elements in all the buildings. The first one is the use of floor-to-ceiling glass windows on steel frames that go around the corners of the buildings without a visible (most of the time without any) structural support. The other unifying element is the use of brick. All buildings have a base of about 40 cm of black brick and the rest is built of yellow bricks. The combined effect is a feeling of lightness or as Gropius called it “etherealization”.

In order to enhance this feeling of lightness, Gropius and Meyer used a series of optical refinements like greater horizontal than vertical elements on the windows, longer windows on the corners and taller windows on the last floor.

The design of the building was oriented to the railroad side. Benscheidt considered that the point of view of the passengers on the trains was the one that determined the image of the building and placed great weight on the facade on that side. It was already noted by Peter Behrens (with whom Gropius and Meyer were working one year before starting work on the Fagus factory) that architects should take account of the way the speed of modern transportation affects the way architecture is perceived. Gropius had also commented the subject in his writings. According to the historian of architecture Annemarie Jaeggi these thoughts were important in the design of Fagus:

In order to enhance this feeling of lightness, Gropius and Meyer used a series of optical refinements like greater horizontal than vertical elements on the windows, longer windows on the corners and taller windows on the last floor.

The design of the building was oriented to the railroad side. Benscheidt considered that the point of view of the passengers on the trains was the one that determined the image of the building and placed great weight on the facade on that side. It was already noted by Peter Behrens (with whom Gropius and Meyer were working one year before starting work on the Fagus factory) that architects should take account of the way the speed of modern transportation affects the way architecture is perceived. Gropius had also commented the subject in his writings. According to the historian of architecture Annemarie Jaeggi these thoughts were important in the design of Fagus:

“The animated fluctuation in height, the change between horizontal structure and vertical rhythms, heavy closed volumes and light dissolved fabrics, are indicators of an approach that deliberately utilized contrasts while arriving at a harmony of opposites in a manner best expressed as a pictorial or visual structure created from the perspective of the railroad tracks.”

After spending two years in the office of Peter Bebrens, Walter Gropius (1883-1969) established his own practice in Berlin. In 1911 he joined forces with his partner Adolph Meyer (1881-1929) to build a factory for the Fagus Shoe Company at Alfeld-an-der-Leine. The Fagus building represents a sensational innovation in its utilization of complete glass sheathing even at the corners. In effect, Gropius here had invented the curtain wall that would play such a visible role in the form of subsequent large-scale twentieth-century architecture.

Gropius and Meyer were commissioned to build a model factory and office building in Cologne for the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition of arts and crafts and industrial objects. Gropius felt that factories should possess the monumentality of ancient Egyptian temples. For one façade of their "modern machine factory," the architects combined massive brickwork with a long horizontal expanse of open glass sheathing, the latter most effectively used to encase the exterior spiral staircases at the corners. The pavilions at either end have flat overhanging roofs derived from Frank Lloyd Wright, whose work was known in Europe after 1910, and the entire building reveals the elegant and disciplined design that became a prototype for many subsequent modern buildings.

Gropius and Meyer were commissioned to build a model factory and office building in Cologne for the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition of arts and crafts and industrial objects. Gropius felt that factories should possess the monumentality of ancient Egyptian temples. For one façade of their "modern machine factory," the architects combined massive brickwork with a long horizontal expanse of open glass sheathing, the latter most effectively used to encase the exterior spiral staircases at the corners. The pavilions at either end have flat overhanging roofs derived from Frank Lloyd Wright, whose work was known in Europe after 1910, and the entire building reveals the elegant and disciplined design that became a prototype for many subsequent modern buildings.

GROPIUS, Walter Adolph (1883-1969)

Walter Gropius was one of the most important architects and educators of the 20th century. The son of a successful architect, Gropius received his professional training in Munich. After a year of travel through Spain and Italy, he joined the office of Peter Behrens, the most important European architect of the day, in Berlin. In 1910, Gropius left Behrens to work in partnership with Adolf Meyer until 1924-25. This period was the most fruitful of Gropius's long career; he designed most of his significant buildings during this time. The Fagus factory in Alfeld-an-der-Leine (1911) immediately established his reputation as an important architect. Notable for its extensive glass exterior and narrow piers, the facade of the main wing is the forerunner of the modern metal and glass curtain wall. The omission of solid elements at the corners of the structure heightens the impression of the building as a glass-enclosed, transparent volume.

In his next major work, the Administration Building for the Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne (1914), Gropius carried the idea further by glazing the entire facade including the corner stairwells. His entry in the Chicago Tribune competition of 1922 was an application of these principles to skyscraper design. In contrast to the winning Gothic design by Raymond Hood, Gropius's solution was free of all eclectic or historical detail. Using the rectangular Chicago window employed by architects like Louis Sullivan, Gropius offered a significant European solution to the design problem posed by America's most innovative structure, the skyscraper.

Gropius's educational philosophy encompassed the designing of all functional objects. His goal was to raise the level of product design by combining art and industry. Although these principles were inherited from English reformers like William Morris, Gropius was able to implement them when he reorganized the Arts and Crafts School in Weimar, which became the world-famous Bauhaus. The unique educational program of the school sought a balance between practical training in the crafts and theoretical training in design. The integration of the arts was stressed, as is evidenced by the faculty who were attracted there--Josef Albers, Marc Chagall, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy.

In 1925 the Bauhaus was forced to move to Dessau, where a landmark of modern architecture was constructed: the Bauhaus in Dessau (1925-26). Asymmetrical in its overall composition, the Bauhaus consists of several connected buildings, each containing an important part of the school (including administration, classrooms, and studio space). The workshop wing, a 4-story glazed box, is the most striking part of the complex.

With Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1933, Gropius fled to England, where he practiced briefly with Edwin Maxwell Fry. In 1937, Gropius was appointed to teach at Harvard. In 1946 he formed a group called the Architects Collaborative, which executed many important commissions, including the Harvard Graduate Center (1949), the U.S. Embassy in Athens (1960), and the University of Baghdad (1961). He was widely respected as a teacher and designed a number of American buildings, including the Harvard University Graduate Center (1950). He designed the Pan Am Building (1963) in New York City in collaboration with the Italian-American architect Peitro Belluschi. Gropius espoused collaborative effort in the design process and founded a firm that he worked with until his death in Boston on July 5, 1969.

http://www.germanheritage.com/biographies/atol/gropius.html

http://www.dipity.com/tickr/Flickr_walters/

http://www.dipity.com/tickr/Flickr_walters/

Al deze foto's komen uit een boek dat ik gevonden heb in het NAI over Walter Gropius.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten